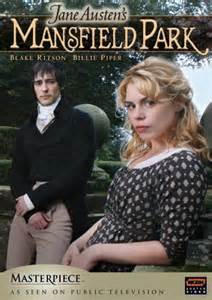

No, this is not another movie review (although I will be writing something about Love and Friendship next time). Think more Mansfield Park.

No, this is not another movie review (although I will be writing something about Love and Friendship next time). Think more Mansfield Park.

This past Saturday, June 25th, I presented a program on Jane Austen at my local library: “Twenty-first Century Jane” – how movies, sequels, and modern variations are helping to carry her popularity into the new millennium. As part of my preparations for the program, I watched (or rewatched) several of the film adaptations, including two of Mansfield Park. And because the book I’m currently working on (see Work-in-Progress page) will have a MP angle to it, I paid close attention.

Since then, I’ve been thinking about Fanny Price and, more specifically, that unfortunate episode of amateur theatrics. You may remember that while Sir Thomas was gone to Antigua, Tom Bertram and his friend Mr. Yates cooked up the idea of putting on a play at home, just to amuse themselves, and they recruited the Miss Bertrams, the Crawfords, and Mr. Rushworth to join in. They were soon assigning parts and making all kinds of plans, including sets and costumes.

Sounds like harmless fun, right? I think it’s difficult, especially for today’s readers, to understand why Edmund Bertram and Fanny Price were so strongly opposed to the idea. And Jane Austen disapproved too, from how she writes. That may be the most surprising part, since the Austen family is known to have done the same – entertained themselves by creating and acting out amateur theatricals at home.

Sounds like harmless fun, right? I think it’s difficult, especially for today’s readers, to understand why Edmund Bertram and Fanny Price were so strongly opposed to the idea. And Jane Austen disapproved too, from how she writes. That may be the most surprising part, since the Austen family is known to have done the same – entertained themselves by creating and acting out amateur theatricals at home.

So what’s the difference here? I decided to look a little deeper into the business.

Edmund objected at once, saying he was certain Sir Thomas wouldn’t approve of his children acting. In a house where the head of the family’s word was law, that should have been enough. Tom chose to disregard what he knew to be true, though.

Then, to compound their error, the company of players made another bad choice. They decided to do Lovers’ Vows. (Presumably, the Austen family never chose to perform this kind of material.)

The first use [Fanny] made of her solitude was to take up the volume [of “Lovers’ Vows”] which had been left on the table, and begin to acquaint herself with the play of which she had heard so much. Her curiosity was all awake, and she ran through it with an eagerness which was suspended only by intervals of astonishment, that it could be chosen in the present instance—that it could be proposed and accepted in a private Theatre! Agatha and Amelia appeared to her in their different ways so totally improper for home representation—the situation of one, and the language of the other, so unfit to be expressed by any woman of modesty, that she could hardly suppose her cousins could be aware of what they were engaging in; and longed to have them roused as soon as possible by the remonstrance which Edmund would certainly make. (Mansfield Park, chapter 14)

In the book and film adaptations, we get little snippets of dialogue as the rehearsals progress, and we see the trouble it creates. But I was still wondering what was so astonishing and improper (according to Fanny in the excerpt above) about the play itself. I found it online and read it. It is a real play, btw, which undoubtedly Jane Austen had read herself. (Read it here if you’re interested)

In the book and film adaptations, we get little snippets of dialogue as the rehearsals progress, and we see the trouble it creates. But I was still wondering what was so astonishing and improper (according to Fanny in the excerpt above) about the play itself. I found it online and read it. It is a real play, btw, which undoubtedly Jane Austen had read herself. (Read it here if you’re interested)

It didn’t seem so astonishing to me at first (not compared to what we’ve become accustomed to seeing in movies and on TV every day): a woman, who had been seduced by a nobleman under promise of marriage, was instead abandoned by him to raise their son alone in poverty. Twenty years later, just when she is near starving to death, her son chances to meet the baron, whom he discovers to be his father, etc., etc.

It takes a lot more than that to shock us these days. But consider that the story of Mansfield Park was taking place in a very different age and culture.

Although these sorts of things happened, even then, they were not talked of in polite society. Children of gentility – the girls at least – were carefully sheltered and guarded. And a career on the stage was absolutely out of the question for anyone from a good family. So to have the daughters of Sir Thomas Bertram participating in a play, especially when it meant that one of them would be posing as and speaking the part of the unwed mother of an illegitimate child, was shockingly bad indeed. Not to mention that the actress (Maria, in this case) would be embracing an actor who was definitely NOT her son or even the man she was engaged to, but bad boy Henry Crawford instead…

The only thing that could have made the situation worse was to have outsiders present to witness the impropriety, which is what Edmund finally consented to taking a role in the play to prevent.

So, Edmund and Fanny were right all along; the acting scheme was a bad idea, at least within the given context. Tom and Maria, who were in denial before, knew it by their guilty consciences as soon as their father returned home unexpectedly. But in the end it wasn’t the words of the play that caused the real trouble; it was the permission the activity granted for bad behavior – all that close contact and sneaking off to “rehearse” in private. There’s little doubt it contributed to what ultimately happened: Maria being ruined by deciding to leave her husband to run off with Henry Crawford.

So, Edmund and Fanny were right all along; the acting scheme was a bad idea, at least within the given context. Tom and Maria, who were in denial before, knew it by their guilty consciences as soon as their father returned home unexpectedly. But in the end it wasn’t the words of the play that caused the real trouble; it was the permission the activity granted for bad behavior – all that close contact and sneaking off to “rehearse” in private. There’s little doubt it contributed to what ultimately happened: Maria being ruined by deciding to leave her husband to run off with Henry Crawford.

So, what I want to know is where was Mrs. Norris???

Throughout the entire book she has been poking her nose into the Bertram family business, telling everybody what to do and not do, claiming to be upholding propriety and guarding against wasteful spending. Now, when we really need her to intervene, she fails us. Well, not us, but she does fail the Bertrams, especially Maria who is her favorite.

Throughout the entire book she has been poking her nose into the Bertram family business, telling everybody what to do and not do, claiming to be upholding propriety and guarding against wasteful spending. Now, when we really need her to intervene, she fails us. Well, not us, but she does fail the Bertrams, especially Maria who is her favorite.

Doesn’t it seem inconsistent that she not only allowed the acting scheme to go forward but assisted in it? Or was she blinded, like so many people are, by the bright lights and the chance to see her darling Maria shine on stage? All I can say is, “Badly done, Mrs. Norris. Badly done indeed!”

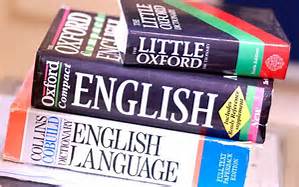

English is not a static language. It’s constantly changing, whether we like it or not.

English is not a static language. It’s constantly changing, whether we like it or not. Actually, her language is one of the aspects of her books I enjoy the most. But emulating it as faithfully as possible has gotten me into some trouble. For instance, one reviewer on Amazon severely berated me for more than once using the word “saloon” in The Darcys of Pemberley, assuming it was a typo and that I surely meant “salon” instead. According to the definitions given in my 2004 Webster’s Encarta Dictionary (and every American western movie ever made), she would be right.

Actually, her language is one of the aspects of her books I enjoy the most. But emulating it as faithfully as possible has gotten me into some trouble. For instance, one reviewer on Amazon severely berated me for more than once using the word “saloon” in The Darcys of Pemberley, assuming it was a typo and that I surely meant “salon” instead. According to the definitions given in my 2004 Webster’s Encarta Dictionary (and every American western movie ever made), she would be right. However, my higher authority was Pride and Prejudice (which possibly the outspoken reviewer had never actually read???). In this excerpt from chapter 45, Elizabeth and Mrs. Gardiner have just arrived at Pemberley at the invitation of Miss Darcy:

However, my higher authority was Pride and Prejudice (which possibly the outspoken reviewer had never actually read???). In this excerpt from chapter 45, Elizabeth and Mrs. Gardiner have just arrived at Pemberley at the invitation of Miss Darcy: At least in this example my use of a troublesome word, whose meaning had changed over time, was only regarded as a typographical error. I got into more serious trouble with “intimate.” Austen used it 100+ times in her writings, and as far as I can tell, not once did she mean anything sexual by it. Yet, when in TDOP I have Darcy telling Elizabeth that it’s unfortunate she once had a rather “intimate” association with Wickham, noisy protests arose from more than one quarter. “Elizabeth would never!” “Darcy wouldn’t believed her capable of such a thing!” Obviously, some readers thought the word inferred a sexual relationship not intended by the author or by Mr. Darcy either. Yikes!

At least in this example my use of a troublesome word, whose meaning had changed over time, was only regarded as a typographical error. I got into more serious trouble with “intimate.” Austen used it 100+ times in her writings, and as far as I can tell, not once did she mean anything sexual by it. Yet, when in TDOP I have Darcy telling Elizabeth that it’s unfortunate she once had a rather “intimate” association with Wickham, noisy protests arose from more than one quarter. “Elizabeth would never!” “Darcy wouldn’t believed her capable of such a thing!” Obviously, some readers thought the word inferred a sexual relationship not intended by the author or by Mr. Darcy either. Yikes! A case in point. The lady in charge of a manor house in those days was the estate’s “housekeeper.” That’s what she was called; there’s no other word I can use for her. As the highest ranking position to which any female employee could aspire, the title carried with it a great deal of respect among the staff and also from the family they served. But unless the reader understands that, they will likely think of someone down on her knees scrubbing floors instead of what she really was: an important member of the household’s management team. I guess there’s nothing I can do about that.

A case in point. The lady in charge of a manor house in those days was the estate’s “housekeeper.” That’s what she was called; there’s no other word I can use for her. As the highest ranking position to which any female employee could aspire, the title carried with it a great deal of respect among the staff and also from the family they served. But unless the reader understands that, they will likely think of someone down on her knees scrubbing floors instead of what she really was: an important member of the household’s management team. I guess there’s nothing I can do about that. Every Jane Austen novel reminds us of the severe limitations society placed on females of genteel birth in her era. About their only honorable option was to become some gentleman’s wife. Although the men had a far better lot in general, their choices were also very restricted.

Every Jane Austen novel reminds us of the severe limitations society placed on females of genteel birth in her era. About their only honorable option was to become some gentleman’s wife. Although the men had a far better lot in general, their choices were also very restricted. Better give that boy something to do! Joining the clergy was acceptable, but not stylish. A military life held more prestige, but also more danger (Napoleon and all). So, perhaps the law? Fine, but then he must be a swanky London barrister, and not (heaven forbid!) a humble country attorney like Lizzy’s uncle Phillips in Pride and Prejudice, who was considered one of her “low connections.”

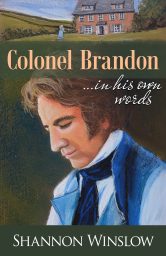

Better give that boy something to do! Joining the clergy was acceptable, but not stylish. A military life held more prestige, but also more danger (Napoleon and all). So, perhaps the law? Fine, but then he must be a swanky London barrister, and not (heaven forbid!) a humble country attorney like Lizzy’s uncle Phillips in Pride and Prejudice, who was considered one of her “low connections.” Although I’m no expert, from what I’ve read, the haphazard education of lawyers seems only a symptom of a much larger malaise afflicting the legal system that existed at the time. Jo Walker (heroine of my book For Myself Alone) has this to say about it:

Although I’m no expert, from what I’ve read, the haphazard education of lawyers seems only a symptom of a much larger malaise afflicting the legal system that existed at the time. Jo Walker (heroine of my book For Myself Alone) has this to say about it: What’s in a name? No, wait, that’s Shakespeare. Wrong author! I’m supposed to be channeling Jane Austen! Let me try again.

What’s in a name? No, wait, that’s Shakespeare. Wrong author! I’m supposed to be channeling Jane Austen! Let me try again. I guess I’m not the only one who has struggled with indecisiveness in this area. Jane Austen changed the titles to at least three of her books before publication. First Impressions became Pride and Prejudice. Elinor and Maryanne became Sense and Sensibility. Northanger Abbey underwent the most transformations. Austen originally called it Susan, after the heroine. Then she changed not only the title of the novel but the heroine’s name to Catherine to avoid confusion with another book that had come out. It was ultimately published as Northanger Abbey after her death.

I guess I’m not the only one who has struggled with indecisiveness in this area. Jane Austen changed the titles to at least three of her books before publication. First Impressions became Pride and Prejudice. Elinor and Maryanne became Sense and Sensibility. Northanger Abbey underwent the most transformations. Austen originally called it Susan, after the heroine. Then she changed not only the title of the novel but the heroine’s name to Catherine to avoid confusion with another book that had come out. It was ultimately published as Northanger Abbey after her death. I don’t really intend my blog to turn into a movie review site, but there has been more than the usual amount of activity in the period movie arena lately, begging some kind of response. (See

I don’t really intend my blog to turn into a movie review site, but there has been more than the usual amount of activity in the period movie arena lately, begging some kind of response. (See  I shouldn’t admit my other thought at the time, which was, “Darn! Why didn’t I come up with the idea first?” I wouldn’t really have been interested in spending that much time thinking and writing about zombies, but I wouldn’t mind the paychecks associated with the franchise.

I shouldn’t admit my other thought at the time, which was, “Darn! Why didn’t I come up with the idea first?” I wouldn’t really have been interested in spending that much time thinking and writing about zombies, but I wouldn’t mind the paychecks associated with the franchise. “Do you think any consideration would tempt me to accept the man who has been the means of ruining, perhaps forever, the happiness of a most beloved sister?” As she pronounced these words, Mr. Darcy changed colour; but the emotion was short, for Elizabeth presently attacked with a series of kicks, forcing him to counter with the drunken washwoman defense. She spoke as they battled: “I have every reason in the world to think ill of you…” (Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, Jane Austen and Seth Grahame-Smith)

“Do you think any consideration would tempt me to accept the man who has been the means of ruining, perhaps forever, the happiness of a most beloved sister?” As she pronounced these words, Mr. Darcy changed colour; but the emotion was short, for Elizabeth presently attacked with a series of kicks, forcing him to counter with the drunken washwoman defense. She spoke as they battled: “I have every reason in the world to think ill of you…” (Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, Jane Austen and Seth Grahame-Smith) I watched two new movies this past week – first the Hallmark Channel’s Unleashing Mr. Darcy and then, a couple of days later, I rented the recently released version of Far From the Madding Crowd.

I watched two new movies this past week – first the Hallmark Channel’s Unleashing Mr. Darcy and then, a couple of days later, I rented the recently released version of Far From the Madding Crowd. Let’s begin with

Let’s begin with  Far From the Madding Crowd

Far From the Madding Crowd Anyway, I watched Far From the Madding Crowd twice before being forced to return it. Now it’s at the top of my wish list for what my husband or sister can get me for my birthday in a few weeks. I can hardly wait to file it in the F section of my collection between The Family Man and Father Goose!

Anyway, I watched Far From the Madding Crowd twice before being forced to return it. Now it’s at the top of my wish list for what my husband or sister can get me for my birthday in a few weeks. I can hardly wait to file it in the F section of my collection between The Family Man and Father Goose! I hope you have all enjoyed your Christmas celebrations, in whatever form they take for you. What a busy time of year! But now that things have eased a bit, I thought I’d relate a special highlight for me from earlier this month. As of a couple of weeks ago, I can now add “playwright” to my resume!

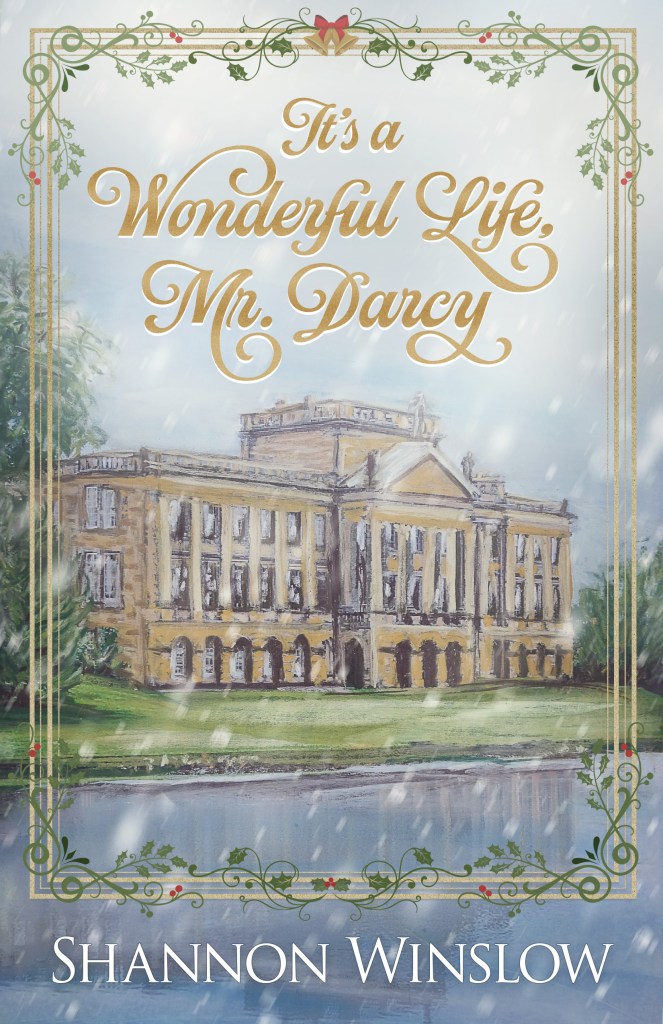

I hope you have all enjoyed your Christmas celebrations, in whatever form they take for you. What a busy time of year! But now that things have eased a bit, I thought I’d relate a special highlight for me from earlier this month. As of a couple of weeks ago, I can now add “playwright” to my resume! One reader suggested – jokingly at first and later seriously – that the sketch would make a “delightful reading” at a meeting of her Vancouver, Canada, JASNA group. I gave my permission, and it was performed in full costume at their December 12th get together as part of the celebration of Jane Austen’s birthday (Dec. 16th). So I think that officially makes me as a playwright, don’t you?

One reader suggested – jokingly at first and later seriously – that the sketch would make a “delightful reading” at a meeting of her Vancouver, Canada, JASNA group. I gave my permission, and it was performed in full costume at their December 12th get together as part of the celebration of Jane Austen’s birthday (Dec. 16th). So I think that officially makes me as a playwright, don’t you? Here Mrs. Gardiner impatiently interrupted, giving her husband’s arm a vigorous shake for emphasis. “Not the fish! It is your opinion of the man I am far more interested in. What say you about your host Mr. Darcy?”

Here Mrs. Gardiner impatiently interrupted, giving her husband’s arm a vigorous shake for emphasis. “Not the fish! It is your opinion of the man I am far more interested in. What say you about your host Mr. Darcy?” Take a bow, Phyllis and Lindsay! (See news blurb about their performance

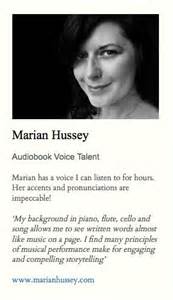

Take a bow, Phyllis and Lindsay! (See news blurb about their performance  Yea! I’m thrilled to say that my latest novel – Miss Georgiana Darcy of Pemberley – is now available in audio format!

Yea! I’m thrilled to say that my latest novel – Miss Georgiana Darcy of Pemberley – is now available in audio format! She studies the material ahead of time with some general direction from me as to how I see the characters and what I want. In this case, since Marian had already narrated my previous two P&P sequels (The Darcys of Pemberley and Return to Longbourn), I just requested that she voice the characters the same way to make the transition from book to book as seamless as possible for the reader/listener. After she had recorded the book, I “proof listened” to it, noting the changes I wanted as I went along. Once I was satisfied, the entire audio book had to go through a final quality control review before being released.

She studies the material ahead of time with some general direction from me as to how I see the characters and what I want. In this case, since Marian had already narrated my previous two P&P sequels (The Darcys of Pemberley and Return to Longbourn), I just requested that she voice the characters the same way to make the transition from book to book as seamless as possible for the reader/listener. After she had recorded the book, I “proof listened” to it, noting the changes I wanted as I went along. Once I was satisfied, the entire audio book had to go through a final quality control review before being released. entertainment. She refers to it in this passage from chapter 14 of Pride and Prejudice, for example. Unfortunately, this is not a very resounding endorsement of the entertainment, thanks to Mr. Collins’s limitations:

entertainment. She refers to it in this passage from chapter 14 of Pride and Prejudice, for example. Unfortunately, this is not a very resounding endorsement of the entertainment, thanks to Mr. Collins’s limitations: I’m not quite sure of the context, except that I’m assuming this letter is to one of Jane’s many nieces and that the Henry mentioned is Jane’s brother. In any case, Jane apparently found Henry’s sermons much more worth listening to than Fordyce’s!

I’m not quite sure of the context, except that I’m assuming this letter is to one of Jane’s many nieces and that the Henry mentioned is Jane’s brother. In any case, Jane apparently found Henry’s sermons much more worth listening to than Fordyce’s!